Post War Reflections

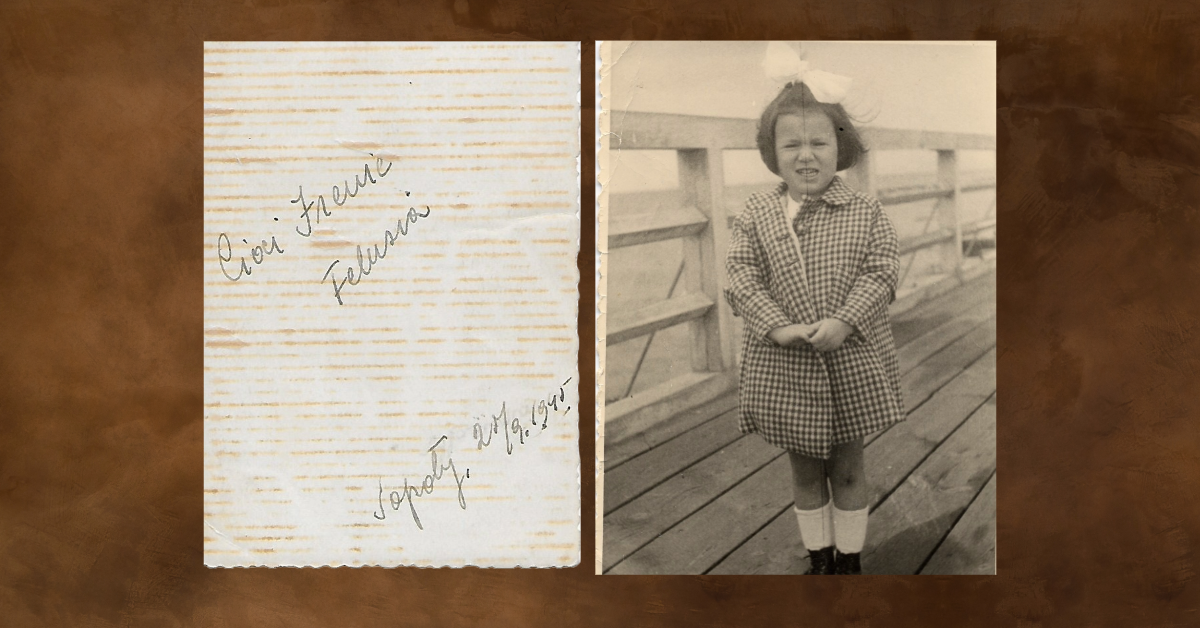

“Cioci Frenie, Felusia; Sopoty, 20/9/1945” – “To Aunt Frenia, Felusia; Sopot, 20/9/1945” reads the back of a photograph I found while rummaging through my parents’ photo box. I am “Felusia” as I am called in Polish, and we lived in Sopot, Poland after liberation. But who is “Aunt Frenia”? I have no idea who she might be. I have no recollection of my parents ever mentioning that name. She could not be a real aunt, because the only one I had when the war started in September 1939 disappeared among the six million Jewish martyrs.

If the picture were for “Aunt Frenia,” what was it doing among my parents’ belongings? I guess I will never know the answers to this question.

In the picture, I am five years old. It is a chilly, cloudy and dreary day, I am standing on a pier in Sopot. The North Sea in the background supplements the dark mood of the shot. You can almost feel the cold wind blowing through my hair. I am holding my black and white checkered coat closed with my hands clasped in front of me. A big white bow sits on top of my hair; white knee socks and ankle high lace-up shoes complete my outfit. It seems I remember that coat. It was thin, providing little warmth. The grimace on my face reflects the weather and the mood. It is probably the best I could muster when told to smile.

I should have been happy. The war was over. My father had found a nice apartment for us. He even found a beautiful doll for me, my first. I still remember the first time I saw her. My mother and I walked into the bedroom I was to share with my parents, and there she was – enthroned on their big bed. She had long black hair, wore a pink outfit trimmed with black lace and a matching pink hat. She looked like a true princess. I still remember my cry of joy and wonder when I saw this beautiful creature. Unfortunately, I do not remember having ever played with her. I guess I either felt that she was too precious to be handled or just simply that I did not know how, did not know what to do with her.

However, when I think back on those days, being happy is not a feeling that I recall. Lonely is what comes to mind. When I look back at the picture, I look stranded, abandoned, all alone on that dreary, windy day. I cannot think of having any friends then or during the two years we spent in Sopot.

I was enrolled in the city’s music academy and was forced to take piano lessons. One day, I walked so slowly to my class that when I arrived, my time slot was over. That scheme proved to be the last one I pulled as I was severely admonished. A happy recollection I do have from that period is playing with our German shepherd, Tommy. He was my friend and protector. Another pleasure for me was to be awakened early in the morning during the summer months to go kayaking with my father.

In the fall of 1947, two and a half years after liberation, I was again cast into a new state. My father was being harassed and threatened by the new Communist regime as a “capitalist.” We had to abandon everything and seek political asylum in Belgium to avoid being sent to Siberia.

I had to adapt to a new home, a new language, a new religion and family relationships. For the last five years, I was raised as a Catholic. My mother and I “hid on the surface,” living as non-Jewish Poles. During my transformation into a Catholic, I was told my father was a Polish Army officer, Josef Slusarczyk, missing in action.

In reality, he remained in the Tarnow ghetto. He managed to escape in the fall of 1943 and joined us in Warsaw. He had IDs under the name of Andrzej Bialecki and was posing as a Polish railroad worker. As I did not recognize him, I was told that he was a “friend.”

Now, in the fall of 1947, in Brussels, the truth of our relationship as well as of my heritage was revealed to me and a new way of life began.

Please leave your comments below.

Read more by Felicia Graber.