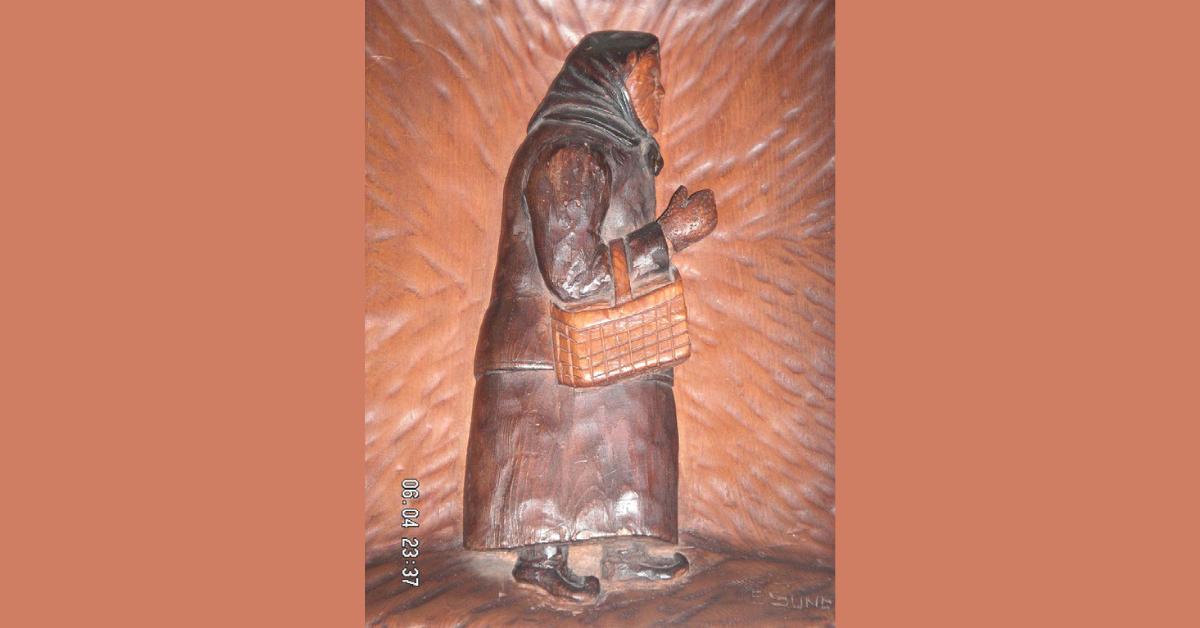

The Old Woman

I call the woodcarving that hangs in my dining room “The Old Woman.” She is ugly. Nobody wants her. Nobody likes her but me. My husband dislikes her; I offered her to my children, but they refused to take her. “She is hideous and depressing,” they both said, their feelings echoed by their respective spouses. But I like her, so I just hung her in my dining room, opposite my chair, where I can see her almost daily.

Why do I like her? What attracts me to her, even though, I admit, she reminds me of an old witch?

She hung in my parents’ apartment in the 1950s in Frankfurt, Germany, when I was growing up. The carving reflects my father’s tastes for exotic art, Russian and Asian antiques and anything that is different or out of the ordinary. She hung in my parents’ living room, and still makes that area come alive for me.

That section of the apartment had many functions simultaneously—music room where I practiced piano, bedroom where I slept on the sofa bed, den where our first television set took center stage and sitting room where we entertained friends. But, for me, that area reverberates mostly with memories of our annual Passover Seder.

I remember as if it is happening today:

The table is set with mother’s best linen, china and crystal. Our guests, all Polish Holocaust survivors, are seated at an extended table. Mother is hurrying back and forth bringing in tureens and platters from the kitchen. And Father… Father sits at the head of that table leading all assembled in the ritual reciting of the Haggadah—the story of the liberation of the Hebrew slaves from Egyptian bondage. He recites whole passages in Hebrew without even glancing at the text; he still remembers it all by heart. He sings the traditional tunes to his heart’s and his guests’ delight and intersperses it all with stories from the “old days,” from the days before 1939, from the days before the war, from a world that has disappeared—the world of Polish Jewry.

I remember Father talking about his beloved father, a Chassid (a member of a branch of Orthodox Judaism), who wore a shtreimel (a fur hat) and a silk bekishe (a long silk coat) on the Sabbath and immersed himself in the mikvah (ritual bath) every morning. Father delights in relating stories of how Chassidim tried to outdo each other in telling tall tales about what marvelous deeds their rebbe (term for rabbi used in that community) was capable of performing. One favorite was the following:

“Several Chassidim were comparing their rebbes’ miracles, each tale surpassing the previous one. One of them was listening quietly, when finally, he said, ‘All your tales are nothing compared to the miracles of my rebbe. He was walking one day and was confronted by a gigantic lion. The lion opened its huge jaws and was about to have my rebbe for lunch. My rebbe stuck his hand into the lion’s mouth, reached for his tail, pulled the tail through the lion’s mouth and turned him around so that he faced away from him.’” The group was speechless.

“How is that possible?” one of them asked.

“Well, you see, it happened,” was the proud reply.

Father also recalls the hassles Jewish boys endured growing up in a small Polish town, the fights in which he had to defend himself and the teachers’ disparaging treatments. Instructors never addressed the Jewish students by name but referred to them as Zydkow (Jew boy). His Jewish education took place in the heder (Jewish religious school) where he learned Hebrew prayers, as well as the Haggadah he can still recite by heart. Above all, however, Father remembers the dire poverty of many Jews who had to borrow a few zlotys (Polish currency) to buy bread for their families.

However, Father always includes one of his many jokes, which illustrate the immense lore of Yiddish humor but also often pokes fun at the Poles among whom Jews lived in uneasy relationship. The following is one was one of Father’s favorites: “A Jew and a Pole were riding on a train. The Pole asked the Jew, ‘Tell me, how come you Jews are so smart?’ The Jew answered, ‘That is because we eat a lot of herring’ ‘Really?’ came the reply. ‘Would it also work for me?’ ‘Sure,’ said the Jew, ‘I happen to have some with me and can sell it to you for 30 zlotys.’ ‘Great,’ answered the Pole. He took out 30 zlotys, got his herring and ate it. Some time went by, and suddenly the Pole said, ‘Say, how come you charged me 30 zlotys for a piece of herring when I can get it on the marketplace for ten?’ ‘You see,’ answered the Jew, ‘It is already working.’”

Almost all Jews in town led a strictly Jewish Orthodox lifestyle. The month before Rosh Hashanah (the Jewish New Year), when Jews recite special prayers at dawn, the synagogue’s sexton would go around town in the Jewish neighborhood, ringing a bell and shouting “Jews, wake up, it is time to go to shul (synagogue) to say selichos (the penitential prayers).”

Yes, that old woman heard many stories during those post-war years, humorous ones and tragic ones of spouses and children murdered. She witnessed celebrations and sad good-byes as friends moved on to the United States, to Argentina or to Brazil when their visas arrived.

And for the last 20 years, she saw the rebirth of those traditions in our dining room here in Baltimore where she hangs—Passover Seders, led by my husband, other Jewish Holidays and birthday celebrations attended by our children and grandchildren.

I hope that someday one of my children or grandchildren will adopt her so that she can witness the unbroken chain of Jewish survival despite Hitler’s attempt to annihilate us.

Read more by Felicia Graber.

Felicia, although I’m sure I read this when you 1st wrote it, I don’t really remember it. Actually, it’s fun revisiting our previous work. I have to admit, I’m not enthralled with your lady, but I do hope one of your family members will feel your relationship to this wood carving and decide to keep it to honor you. If I were your daughter or granddaughter, I’d keep it just because you love it. Linda

I like the “old lady” and the memories she brings. I have several original art works by a great-uncle. The kids probably won’t want them but while they might not be worth a lot of money, they have sentimental value for me.