My Journey to the Past

Part 2

(Part 1 can be read here.)

Three generations, four women, 17 cities and hundreds of experiences. That is a summary of a 10-day trip to my native Poland in June 2005.

My daughter and two oldest granddaughters joined me for a journey of a lifetime. We arrived in Warsaw on three different planes, on three different schedules, from three different cities and two different continents. My daughter, Sarah, and her oldest daughter, Esther, came from Cleveland. My oldest granddaughter, Goldie, traveled from Jerusalem, where she had just finished a year of study at an Orthodox Seminary for girls. I flew in from St. Louis.

I left Poland as a child with my parents, Salomon and Tosia Lederberger, in 1947. My growing up years were filled with stories about my hometown, Tarnow, about my grandparents and about Jewish life in prewar Poland.

I heard about our escape from the ghetto and the heroic acts of my father. I was told about my mother’s travails to keep herself and me alive while we lived as Catholics in Warsaw and during our stay with a farmer family in a tiny Polish village.

I went back to Poland for the first time in 1994, when my husband and I joined a group led by Rabbi Weinreb from Baltimore. That trip was a life-changing event for me. I had no intention of ever going back. I felt that the whole of Poland was a Jewish graveyard and that the so-called rebirth of Polish Jewry was a sad joke. However, as the years passed and my grandchildren grew, I felt the need to expose them to that part of their heritage.

I found Poland to be a very different country after 11 years. She had been accepted into the European Union, and everyone was eager to prove that they were truly Westernized. Jewish tourism had become a major industry. We met Jewish youth groups from the U.S., England, Israel and South America. Municipalities all over were putting up plaques, posters, signs, memorials and markers to commemorate destroyed Jewish synagogues, cemeteries and killing places. Tour guides were trained in all facets of Polish Jewish history and the important historical places. Drawings and paintings of Jewish scenes, wooden statues of chasidim holding Torahs or praying and books in Polish on Jewish religion, culture and history were prominently displayed on all souvenir stands.

The notorious Polish anti-Semitism seemed nonexistent. However, many Poles were quick to point out that millions of their citizens were also murdered by the Nazis in slave labor and concentration camps. Some expressed the desire that tourists not ignore Polish suffering. In the words of one salesgirl, “We also have churches, not only synagogues.”

In 2005, the Jewish community in Poland was growing as well. According to Midrasz, the Polish Jewish monthly, there were about 7,000 Jewish Holocaust survivors in Poland, mostly elderly and impoverished. There were also about 25,000 young Poles of Jewish origin who had relatively recently become aware of their Jewishness. The magazine strived to satisfy the needs of this group with the goal of bringing them closer to Judaism.

Jewish museums were numerous. In addition to the Jewish Historical Museum in Warsaw and the Galizia Museum in Krakow, a Museum of the History of Polish Jews was supposed to open in the near future, as well as a museum in the Oscar Schindler’s former factory. These were besides the many synagogues that have been rebuilt, restored and converted into museums. We saw some in Krakow and in Oswiecim (Auschwitz).

We spent Shabbat morning at the Nozyk Synagogue in Warsaw. Rabbi Michael Schudrich, the Chief Rabbi of Poland, was a young, energetic American, who led the service and delivered his sermon in Polish and English. The congregation consisted of a mixture of chasidim, elderly Holocaust survivors, women in sheitels (wigs) and American youth groups, as well as curious onlookers in all kinds of interesting outfits. A group of at least a dozen children, ages four to six, had the run of the place. They looked like they came straight out of a picture album about “the lost world of Polish Jewry:” payos (long sidelocks), black yarmulkes (skullcaps) for the boys, long sleeve dresses for the girls – all speaking Polish.

To add to this interesting mixture of worshipers, there was a bar mitzvah that Shabbat. The Yemenite family of the Israeli Consul to Warsaw celebrated the event in the truly traditional way of their native country – together with the special Yemenite tunes of the bar mitzvah boy, the typical Mideastern women’s chants and the throwing of the candy from the balcony.

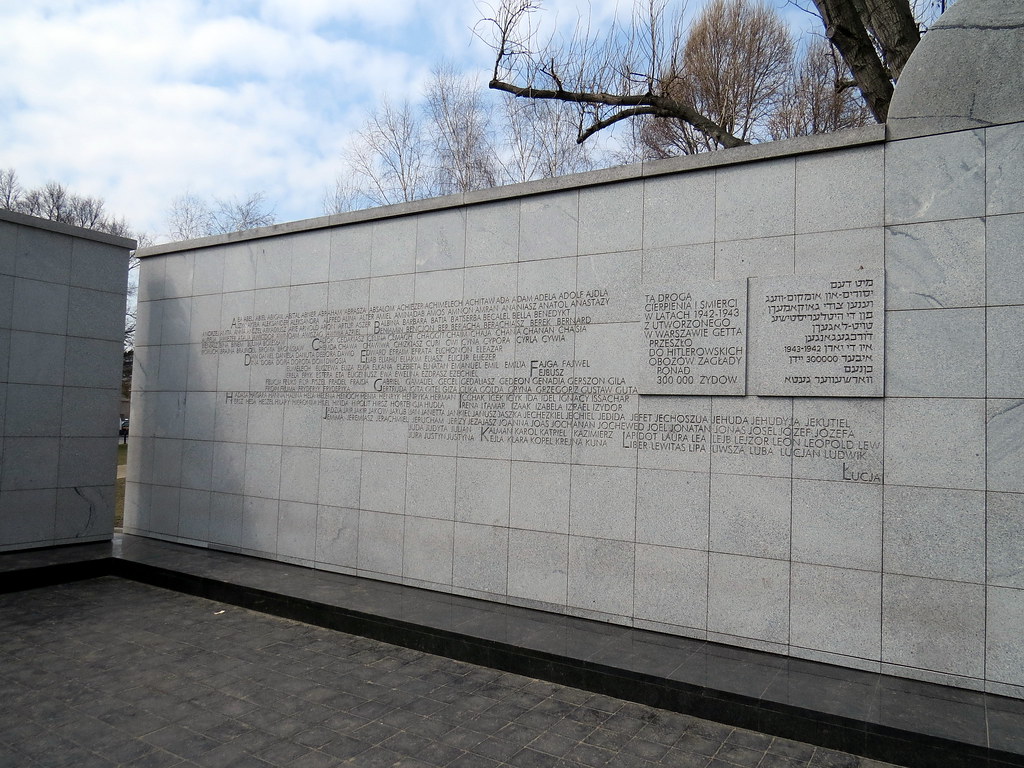

We visited places of Jewish martyrdom in and near Warsaw: the Warsaw Ghetto and memorial, the Umschlagplatz, from where 300,000 Warsaw Jews were sent to their deaths in Treblinka, the death camp nearby. We visited the memorial of Mila 18, the site where the young heroes of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising took their lives in order not to be captured by the Nazis. Later we drove to Wyszkow, the birthplace of Mordechai Anielewitch, the 24-year-old leader of that uprising. The Polish government put up a memorial there in his honor in 2004 – the 60th anniversary of his death.

We stopped by Pruszkow, the notorious German Stalag 121 transit camp where the inhabitants of Warsaw were driven after the failure of the Polish Warsaw Uprising of 1944. From here, most were shipped to Germany for slave labor. My parents and I, as well as some other Jews hiding out as Aryans, were caught up in this dragnet. Today, there is a sign on the old building saying, “Warsaw walked through here in 1944.” It was from this camp, from Pruszkow, that my parents managed to get released, together with me. It was from here that we went on the search for shelter, which we found on a farm near the town of Grodzisk Mazowiecki.

That June, the four of us followed that same path. We arrived in Grodzisk, where the youngest and only surviving member of that farmer family greeted us with hugs and kisses. Janina, a white-haired woman in her mid-seventies, was very happy to see us. I saw her and her older sister on my earlier trip, and we corresponded for the 11 years since my last trip. All along, however, I was certain that she, her sister and their parents did not know that they sheltered a Jewish family. I grew up believing that her father, this good-hearted farmer, was a staunch anti-Semite who thought he was helping poor Polish refugees from bombed-out Warsaw.

With great trepidation I had written Janina the truth about my heritage before this trip, not knowing what reception this would receive. To my great surprise, Janina informed me she and her sister knew all along that we were Jews. It seems that her father somehow figured it out. He took the girls out into the field and made them swear to keep this a secret. He warned them at the same time that if they saw German soldiers coming, they should run for their lives. The Germans’ policy was to shoot not only Jews in hiding but also any Pole who was helping them.

Janina was happy to meet my daughter and granddaughters, considering me her little sister. And thus, as she kept repeating, the girls were her family, too. The five of us went to the farm where we lived those last months of the war. Janina told us about the poor conditions: Seven of us lived in the two-room house. Food was scarce; whatever was grown and whatever eggs the chicken laid were taken to the market to sell. Each farmer had to turn over a part of his food supply to the German authorities. However, in Janina’s words, “We all lived as one family. We managed to have enough so that we did not starve. We survived, and that is what is important.” We stayed with Janina most of the day, and parted with more kisses, hugs, tears and promises to keep in touch.

The next day, on the way south, we stopped in Maidanek concentration camp outside of Lublin. In town, we saw the old Yeshiva (Rabbinical School) Chachmei Lublin. The building was returned to the Jewish community, with hopes to restore it and attract a new generation of students. The small synagogue/museum Chevrat Nossim was closing its doors to tourists; all moneys were being diverted to the rebuilding of the Yeshiva. According to the synagogue’s caretaker, there were about 14 Jews left in Lublin today, all elderly survivors who came there or to the Yeshiva for services.

We drove through Zabno, where my father was born. We stopped in Breszko, where my grandfather was born and where both my great-grandparents are buried. The Polish caretaker of this cemetery sold me a book about the people buried there, and in it I found my great grandmother’s name listed.

One of the most eerie places on the way was the killing site near the small town of Zbylitowska Gora. The memorial plaque eulogizes thousands of Jews who were shot there on June 11, 1942 – the same day my grandparents were deported from Tarnow a few miles away.

We passed Dabrowa Tarnowska, where we accidentally came across a large old synagogue. It was all boarded up, condemned, in danger of collapsing. A sign in front proclaimed that it was to be rebuilt and showed a picture of a once magnificent structure.

Then it was on to Tarnow, my hometown. Before the war, 48% of its inhabitants were Jews. In 2005, there were none. What remained was the bima of the grand old synagogue, which burned for three days after the Germans set fire to it in November 1939, and the Jewish cemetery where my grandmother and great-grandmother are buried. In 1994, I could not find their graves; this time, it took us about two hours to find them and another 30 to 45 minutes for my granddaughters to make a path so we could come close to them.

Then it was on to Krakow. Krakow was not bombed during the war, nor was Kazimier, the center of Jewish life before the war. Within a few blocks, you could visit several restored synagogues: the Rema, where services were held again, the Tempel, the Tall Synagogue, the Izaak Synagogue and the Old Synagogue. The latter two became museums of lost Jewish life and religious memorabilia. Several kosher-style restaurants in the area featured “Jewish style” fish, chicken soup and matzo balls. A klezmer band entertained the diners every evening.

On the outskirts of Krakow is Plaszow, the site of a Jewish cemetery before the war. Sara Scheneirer, the founder of the Bais Yaakov religious education movement for girls, was buried there in 1935. The Nazis destroyed this cemetery and established a concentration camp in its place. A few months before our trip, Sara Scheneirer’s grave was rededicated. The building that housed the first Bais Yaakov still stands and is now a school for deaf children. A plaque commemorates its original use.

And then there is Auschwitz – a tourist showpiece of barbarism, with displays of eyeglasses, shoes, hair and luggage that the Germans did not manage to ship back to the fatherland to be reused.

No trip to Poland would be complete without a pilgrimage to the graves of famous Rabbis to light a candle, say a prayer and maybe leave a written petition.

I can truly say that this trip was a trip of a lifetime, with so many experiences on so many different levels that they took our breath away. It will take many years before I can even think of going back again. Maybe in 10 years, when my two youngest granddaughters will be the same age as Esther and Goldie are now. Who knows? With G-d’s help, it is possible that there will be another trip with three generations.

Please leave your comments below.

Read more by Felicia Graber.

Such an amazing journey, Felicia, physically and emotionally. Thank you once again for sharing it with us and the world.